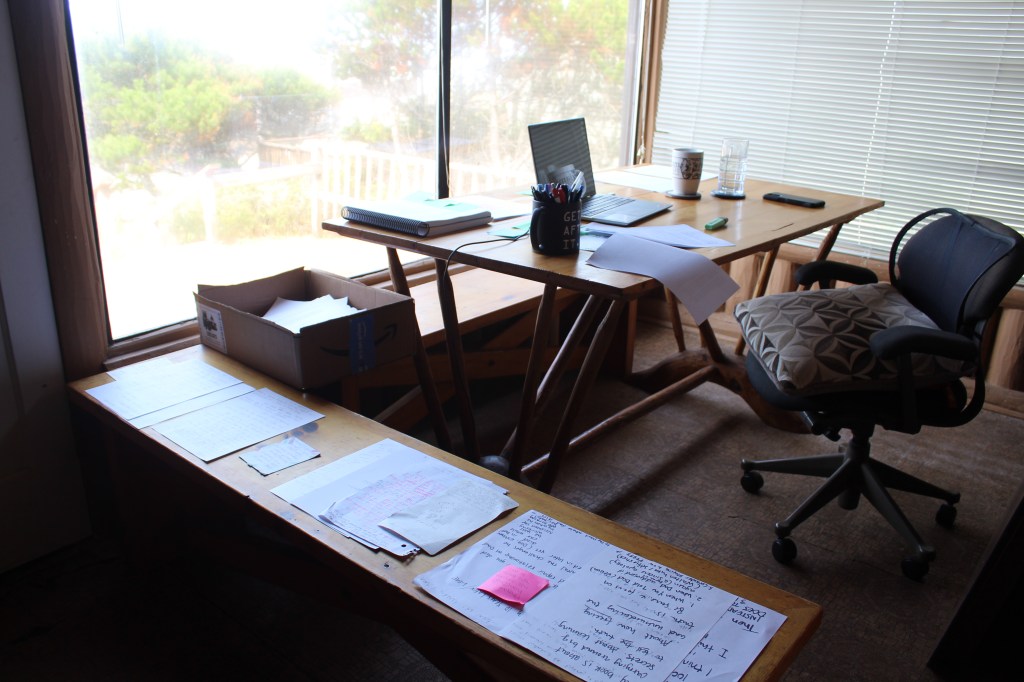

I spend a lot of time with the dead people in my family. Typing that line, I must pause and stare at the word. Dead. It doesn’t jive with how it really is. With how alive they really are. Right now, for example, seated at my maternal great grandmother Glady’s oak stationary desk, it is her short fingers, not mine, I can imagine reaching out to place a paper clip in a small ceramic dish. The ornate, antique desk came into my life unexpectedly when my great aunt recently moved into assisted living, and it is now the most valuable thing that I own. My mind is blown when I consider that I was just five years old when my great grandmother passed away and, shortly before, said she wanted me to have the desk. That was, of course, long before I was a writer.

I didn’t used to believe in the supernatural or in superstitions. Though I have always accepted that dreams hold significant meaning. But since Dad’s passing, and in the months leading up to it, my previous beliefs were challenged. They softened under the weight of the unexpected. I’d have been a fool not to notice the signs.

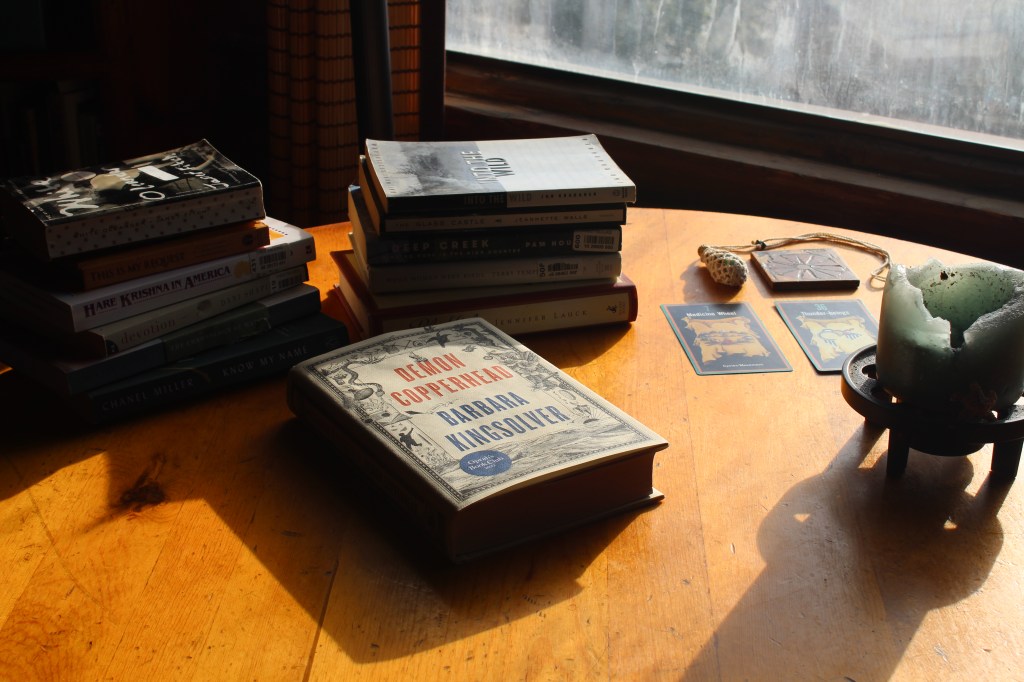

In my notebooks, I’ve written down countless instances that point to a storyline larger than us, one just beyond reach. I’ve experienced things that felt more like serendipity than happenstance. Objects arriving in my life like gifts from the universe. A spectacular and rare seashell washed up on Rockaway Beach, during a week away working on my memoir. A brass bell sitting in the rain. An antique desk.

Not long ago, I awoke from a dream along with a message from my late second cousins, Kathy and Carla, who were more like aunts to me. It was one of the few dreams where I’ve been delivered a very specific message. Such dreams are rare. That’s how I know they’re special. In my dream, I stumbled upon heaven. I intuited that I was in heaven by the fact that Kathy and Carla, who had both died of cancer within five years of each other, where there. In dreamland they signaled it was them because they both wore no hair, a reminder of the cancer that had taken them in this form.

I was surprised to find that heaven was less like a place in the sky where you frolic around, and more like Santa’s workshop. Kathy and Carla weren’t idly hanging out on a cloud, sipping earl grey tea, and catching up with Jesus. No, they were both hunched over some sort of creative project. They were working with their hands. They almost seemed annoyed when I interrupted them. I was surprised to see that actual work was being done in heaven. Upon realizing where I was, I wanted to know things. The pressing question that came to mind was, “How can I accomplish my goal of publishing a book?”

They both looked at me, looked at one another, and then communicated these words: Take the actual steps needed to get there.

When I woke, I thought about their words. Take the actual steps needed to get there. I loved that. The actual steps. Not the fake steps. I wrote it down. Carried it with me. Scheduled another writing retreat. Doubled down on my creative writing projects.

There were more serendipities:

Driving to pick up my wedding dress alone on the day before our ceremony the first song that played when I turned on the radio was “My Sweet Lord” by George Harrison. It was the same song I played in the ICU seventeen days earlier when releasing Dad’s spirit back into the wild.

A few weeks after the ceremony, I’d been bawling my eyes out in the kitchen, and my electric teakettle turned itself on, gently. It was as if Dad was saying “I see you” and “It’s all going to be okay.”

One Monday after returning from California with a trunk full of Dad’s belongings, I stumbled upon a piece of a brass altar set, sitting out in the pouring rain, at work near the bench where I always eat lunch. The brass hand bell was identical in color and detail to the rest of Dad’s altar set, which I had just unpacked and polished the night before. I knew the bell belonged with me, though it felt strange putting it in my pocket and carrying it home. I placed the bell on a shelf with the rest of Dad’s set and it was a perfect match.

Months before Dad’s fatal accident, on a dark winter night, I was at home with my daughter. It was just the two of us. My husband (then fiancé) was out. We live a quarter mile from the highway, nine miles from the nearest general store, and we have one neighbor within earshot. We don’t get a lot of visitors. But when we heard three loud knocks on the front door, I still didn’t think much of it. Sometimes a dog gets lost on our stretch of highway and the owner goes knocking on doors asking if you’ve seen them. Or it could have been the UPS or FedEx man. But when I swung open the front door, no one was there. Autumn and I immediately looked at one another, stunned. I locked both doors and put Autumn to bed. I couldn’t quite get the three knocks out of my mind, so I googled “three knocks ghost.” I read reports from different places across the world about a phenomenon called the “three knocks of death” signaling that someone you know has or soon will die. Some believers went far enough to claim that the death will happen in three days, three weeks, or three months.

I spoke with my cousin Crystal the following week. A vehicle had crashed into our lower pasture at dawn, resulting in a fatality. The family affixed a steel cross on a tree trunk on the opposite side of the highway. I ran across the road to study it. It was a young man who’d died. Just nineteen years old. I told my cousin, “I feel like death is all around me.” Only I whispered it, as if by keeping my worst fears quiet enough, they couldn’t possibly come true. By my estimate it was no more than six months later when I got the call about Dad falling off a ladder at a job site.

Autumn, now five years old, recently approached me with a question. She asked if her and Grandpa Rob ever played with toys together on a rocky beach. I told her that they’d played with toys on a sandy beach at the river. She said this wasn’t at the river, it was at the ocean. She reiterated that it was on a rocky, not a sandy beach. She paused for a moment, then said, smiling, “It must’ve been a dream. But wow, it felt so real.”

I smiled knowing Dad had a hand in that. All Autumn ever did was ask me to play with her. So here he was stepping in when I couldn’t. Maybe our ancestors have the birds-eye view. They can be everywhere all at once. They can see into the future. They can understand the past. My ancestors have always known that I need all the help I can get. Today, I am wide open to receiving their signals.

My great grandmother’s desk came into my life in perfect timing. Just when fear managed to unsettle the well of my creativity, doubts churning in the dark waters. Negative self-talk—and just plain laziness—had manifested itself in the form of my stagnant memoir project. There was the penetrating thought that maybe it all doesn’t matter, anyway. My story. My pile of pain. My gift to the world. But now, this desk. Ancient wood capturing afternoon sunlight, illuminating a blank page. Beckoning. Reminding me that there is enough space in this world for one more story. I only need to be willing to take the actual steps needed to get there.

Love and mysterious blessings,

Mama Bird